Peer Reviewed Articles on Depression in the Elderly

- Inquiry commodity

- Open up Access

- Published:

Prevalence of depressive symptoms among older adults who reported medical cost as a barrier to seeking wellness care: findings from a nationally representative sample

BMC Elderliness volume 19, Article number:192 (2019) Cite this article

Abstruse

Groundwork

Older adults aged 65 and over will brand upwards more than twenty% of U.S. residents by 2030, and in 2050, this population volition reach 83.7 million. Depression amidst older adults is a major public wellness business projected to be the 2d leading cause of disease burden. Despite having Medicare, and other employer supplements, the burden of out of pocket healthcare expenses may be an of import predictor of depression. The current study aims to investigate whether delay in seeing a md when needed merely could not because of medical price is significantly associated with symptoms of current depression in older adults.

Methods

Cross-exclusive data from the 2011 Behavioral Take a chance Cistron Surveillance System (BFRSS) from 12 states and Puerto Rico were used for this written report (north = 24,018).

Results

The prevalence of symptoms of current depression amid older adults who reported medical cost as a barrier to seeking health care was significantly higher (17.8%) when compared to older adults who reported medical cost not being a bulwark to seeking health care (five.5%). Older adults who reported medical cost as a barrier to seeking health intendance were more than likely to study current depressive symptoms compared to their counterparts [Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR): 2.2 [95% CI: 1.5–3.3]).

Conclusions

Older adults (≥ 65 years of age) who experience the brunt of medical cost for health care are significantly more likely to report symptoms of depression. Health care professionals and policymakers should consider effective interventions to improve admission to wellness care among older adults.

Background

The rapid aging of the United States population is due, in part; to the increase in life expectancy and the aging of the post-Earth War II baby boom generation [ane]. By 2030, older adults anile 65 and over will make up more than 20% of U.Southward. residents, and by 2050, this population will attain 83.7 million, almost double the 2012 estimated population of 43.1 million [1, two]. Older adults are disproportionately affected by chronic conditions with approximately 60% living with at to the lowest degree ane chronic condition and 42% with at least two chronic atmospheric condition [3]. Access to health services is essential for prevention and management of chronic illnesses to minimize the affliction burden and associated health care costs. The overarching goal of Healthy People 2020 is to improve the health, function, and quality of life of older adults, which includes an objective to increase the proportion of older adults who are up to date on a cadre prepare of clinical preventive health services for maintaining quality of life and overall health [iv].

Depression is a serious problem and a major public health concern among older adults [5, half-dozen]. The prevalence of depression amid customs dwelling adults aged 65 and older is estimated to be between 5 and 10% and is projected to be the 2d leading cause of disease brunt in this population by the year 2020 [7, 8]. Risk factors for depression such every bit chronic diseases [ix], disability [10, xi], lack of social back up, and socio-economic status [12,thirteen,14], have been well documented. Given that aging is associated with multiple chronic health conditions and limited fiscal resource for illness management, and despite the availability of Medicare, Medicaid and employer supplements [15,sixteen,17,18,19], the burden of out of pocket healthcare expenses may be an important predictor of depression.

Although several studies have documented the risk factors for low in the elderly [ix, 10, 12,13,14], and while others take examined the bear on of low on healthcare costs [20,21,22], to the best of our knowledge, out of pocket healthcare expenses (due east.chiliad., delay in seeing a dr. when needed but could not because of medical cost) as a predictor of current depressive symptomatology in a nationally representative sample of customs-abode older adults in the U.S. has not been documented nevertheless. Previous reported research on the association betwixt financial strain and depressive symptoms among older adults focused on financial strain measured by a four-particular calibration and was not specific to financial strain due to the burden of out of pocket healthcare expenses [23, 24]. Every bit such, the purpose of this study is to:

- (i)

estimate the prevalence of current depressive symptoms in a sample of community dwelling older adults (≥ 65 years of age) who reported a delay in seeing a doc when needed just could not considering of medical toll,

- (2)

investigate whether delay in seeing a physician when needed but could not considering of medical cost is significantly associated with symptoms of current depression in the elderly afterward accounting for possible potential confounders, and.

- (iii)

describe the socio-demographic characteristics of older adults who are more likely to report delay in seeing a doctor when needed only could not because of medical price.

This current study is motivated by "The theory of cost-sharing" framework. Cost-sharing is whatever kind of out-of-pocket expenses made by individuals for health care services. Information technology may result in individuals' delaying a follow-upward health intendance visit or completely expect out a wellness problem [25, 26]. Therefore, we sought to sympathise the human relationship between cost-sharing, equally defined by medical cost as a barrier to seeking health care, on symptoms of current depression which is an important wellness outcome.

Methods

Full general study blueprint

The Behavioral Risk Factor and Surveillance System (BRFSS) is a federally funded telephone survey designed and conducted annually by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in collaboration with state health departments in all l states, Washington, DC; Puerto Rico; the U.S. Virgin Islands; and Guam. The survey collects information on wellness atmospheric condition, preventive health practices, and risk behaviors of the adults selected [27]. All BRFSS questionnaires, data, and reports are available at http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/. Data for this study were obtained from 12 states (Kansas, Louisiana, Maine, Mississippi, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New United mexican states, New York, Ohio, and Oregon) and Puerto Rico that administered the 'Anxiety and Depression' optional module in the 2011 BRFSS data. The weighted response rates ranged from 33.iv to 61.vii%.

Delay in seeing a doctor due to price: primary exposure of interest

To determine if cost is a bulwark to seeking health intendance among older adults, responses to the following question: "Was there a time in the past 12 months when you lot needed to come across a physician just could not because of price? " were used to create a binary exposure variable (Yes / No).

Current depressive symptoms: primary outcome of interest

Electric current depressive symptomatology is defined based on the responses to the eight-item Patient Wellness Questionnaire (PHQ-8) depression scale [28]. The scores for each item, which range from 0 to 3, are summed to produce a total score between 0 and 24 points. Symptoms of current depression is defined every bit PHQ-eight score ≥ 10 [25]. The PHQ-8 consists of 8 of the 9 DSM-IV criteria for depressive disorders [29, xxx].

Covariates of interest

Socio-demographic variables: age, gender (male, female), race/ethnicity (White non-Hispanic, African American non-Hispanic, Hispanic, Others), marital status (married, single), education (less than college, college graduate), and employment (employed, unemployed); Health indicators: general wellness ("Splendid / Very good / Adept" or "Fair / Poor"), use of special equipment due to a health trouble (Yeah / No), smoking (Aye / No), and number of chronic atmospheric condition other than current low; and Health care indicators: having a wellness plan (Yeah / No), having a primary care provider (Aye / No), and having an annual checkup (Yeah / No), were considered as covariates of interest in this report.

Statistical analyses

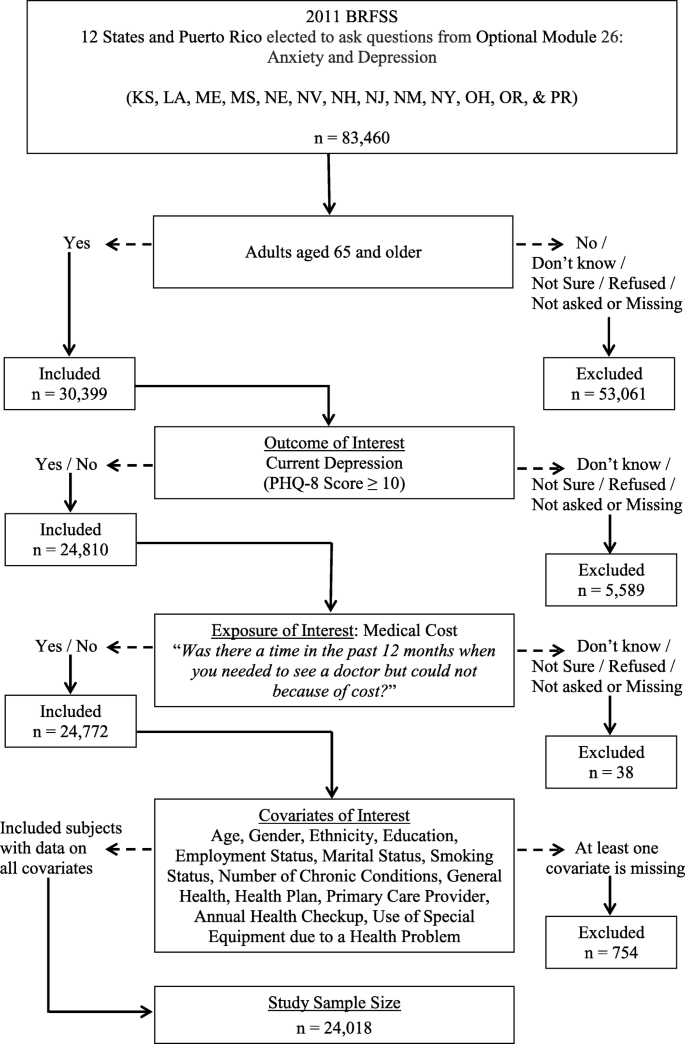

Sampling weights provided in the 2011 BRFSS public-employ information that adjust for unequal selection probabilities, survey not-response, and oversampling were used to account for the complex sampling design and to obtain population-based estimates that reverberate U.Southward. not-institutionalized individuals. In order to describe the characteristics of the study population, weighted prevalence estimates, and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were computed based on the sample of individuals (n = 24,018) with complete data on all variables considered in this written report (Fig. i). Logistic regression models were used to examine if filibuster in seeing a doctor when needed just could not because of medical toll is significantly associated with symptoms of electric current depression in the elderly, adjusting for potential confounders and other covariates.

Flowchart of Written report Population and Sample Size

All analyses were conducted in SAS ix.three (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) using SAS survey procedures (PROC SURVEYFREQ, PROC SURVEYMEANS, PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC) to account for the complex sampling design.

Results

Sample characteristics

In 2011, the prevalence of electric current depressive symptoms among U.Due south. older adults from the 12 states and Puerto Rico was 6.1% (95% CI: five.3–7.0%). Almost half-dozen % (five.7, 95% CI: four.9–six.six%) reported medical toll equally a barrier to seeking health care when needed in the by 12 months. Table i describes the overall characteristics of older adults, the weighted prevalence of reporting medical cost equally a barrier to seeking wellness care and the weighted prevalence of current depressive symptoms along with the corresponding 95% conviction intervals. The average age of older adults at the time of survey was 74.1 years [95% CI: 73.9–74.four]. The bulk of these adults were females (56.3%), White Non-Hispanic (77.v%), and more than three-fourth of them were either retired or unable to work. A little less than half of the older adults were unmarried (48.three%), and had more than high schoolhouse education (44.6%). A piddling over one-fourth of the older adults reported "fair/poor" general health (28.8%), almost 80% of them had at to the lowest degree one chronic condition other than current depression, were predominantly non-smokers (91.2%), and did non use whatever special equipment due to a wellness problem (81.0%). The majority of older adults in the 12 states and Puerto Rico reported having a health program (97.9%), having a master intendance provider (94.vii%), and having an almanac health checkup (87.1%).

Significant sub-groups of older adults with medical cost as a bulwark to seeking health care

Among the unlike covariates examined for meaning differences in the proportion of older adults who reported medical cost as a bulwark to seeking wellness care when needed in the past 12 months, the following sub-groups of individuals were significantly higher in proportion to report medical cost equally a barrier to seeking health care compared to some of the older adults who reported medical cost not being a barrier to seeking health care: i) Hispanics vs. White not-Hispanics (11.vii% vs. 4.iii%); ii) Blackness non-Hispanics vs. White not-Hispanics (x.1% vs. iv.three%); iii) older adults with no higher education vs. those with some higher education (7.ii% vs. iii.9%); iv) those who reported "Off-white/Poor" full general health vs. those with "Excellent/Very Good/Good" full general wellness (10.4% vs. three.8%); v) those with 3 or more chronic conditions other than electric current depression vs. those with no chronic conditions (8.2% vs. 3.8%); vi) smokers vs not-smokers (xi.3% vs. five.2%); vii) those who reported use of special equipment due to a health condition vs. those who did not employ (10.0% vs. iv.7%); eight) those with no health programme vs. those with a health plan (27.iii% vs. five.2%); ix) those with no chief care provider vs. those with a primary intendance provider (11.eight% vs. v.4%); and x) those who reported not having an annual health checkup vs. those who did (11.4% vs. iv.9%). There was no significant difference in the average historic period of older adults who reported medical cost as a barrier to seeking health intendance when compared to those who did non study medical price equally a barrier (73.0 years vs. 74.2 years).

Significant sub-groups of older adults with current depressive symptoms

Females were significantly higher in proportion to written report symptoms of current depression compared to males (seven.4% vs. 4.6%). Amidst the sub-groups of individuals who reported medical cost as a bulwark to seeking health care, the post-obit also reported symptoms of current depression: i) Hispanics vs. White non-Hispanics (xi.0% vs. v.6%); ii) those who reported "Fair/Poor" full general health vs. those with "Excellent/Very Skillful/Skillful" full general health (xiv.3% vs. 2.viii%); iii) those with 3 or more chronic conditions other than electric current depression vs. those with no chronic weather (11.5% vs. ii.8%); iv) smokers vs not-smokers (10.8% vs. 5.7%); and v) those who reported utilize of special equipment due to a wellness condition vs. those who did non use (15.v% vs. iv.0%). Interestingly, older adults with a health plan were significantly higher in proportion for symptoms of electric current low compared to those without a health program (half dozen.2% vs. three.3%). Average age between individuals with and without symptoms of current depression was not pregnant (73.viii years vs. 74.1 years).

Model based odds ratios for symptoms of electric current depression

The prevalence of symptoms of electric current depression among older adults who reported medical cost every bit a barrier to seeking health care was significantly higher [17.8, 95% CI: (11.four–21.one%)] when compared to older adults who reported medical cost non existence a barrier to seeking health care [v.v, 95% CI: (iv.vii–6.ii%)]. After adjusting for all covariates of involvement, older adults who reported medical cost as a barrier to seeking health care were more than than twice probable to written report current depressive symptoms compared to older adults who reported medical toll not being a barrier to seeking health intendance (Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR): two.2 [95% CI: i.5–3.3]) (Table two). Additional file one: Table S1 provides additional details on possible potential confounders we adjusted for in determining the association between medical cost as a barrier to seeking health intendance and current depressive symptoms in older adults.

Predictors of reporting medical cost as a barrier to seeking health care

According to the adapted logistic regression model results, gender (females: AOR: i.52 [95% CI: i.07–ii.17]), ethnicity (Black non-Hispanics: AOR: 1.79 [95% CI: 1.09–2.96]; Hispanics: AOR: ii.48 [95% CI: 1.53–4.02]), teaching (less than college education: AOR: 1.49 [95% CI: i.05–2.10]), general wellness ("Fair / Poor": AOR: 2.12 [95% CI: 1.42–iii.17]), smoking status (smokers: AOR: ane.72 [95% CI: 1.07–ii.76]), having a wellness plan (No: AOR: five.44 [95% CI: 2.67–11.09]), getting an almanac checkup (No: AOR: 2.82 [95% CI: 1.91–4.17]), and use of special equipment due to a health trouble (Aye: AOR: 1.64 [95% CI: 1.13–ii.39]) were significant predictors of reporting medical toll as a barrier to seeking health care (Table 3).

Discussion

Written report overview

Broadly speaking, studies on depression in the elderly have focused either on its risk factors or associated increases in health intendance costs and utilization. The current written report is unique as it represents the first study of its kind to report the prevalence of symptoms of electric current low in a sample of community abode older adults (≥ 65 years of historic period) in the U.Southward. who self-reported medical price every bit a barrier to seeking health care. In addition, this study examined the association between self-reported medical toll as a bulwark to seeking health care and current depressive symptomatology and identified the socio-demographic characteristics of older adults who had a significantly higher likelihood to study medical cost as a barrier to seeking health intendance. The findings from this study highlight the need for effective interventions to address the barriers to seeking health care due to the brunt of out-of-pocket medical cost on the individual, peculiarly for those with multiple chronic weather. This may help minimize the risk for current depression in older adults.

Main findings

Based on data from the 2011 BRFSS, the prevalence of symptoms of electric current depression in a sample of community dwelling older adults (≥ 65 years of age) in the U.Southward. was six.1%. This prevalence is college than previously reported based on data from 2006 BRFSS using similar criteria (score ≥ 10 on PHQ-8) for current depressive symptoms [28]. The prevalence of current depressive symptomatology was significantly college (17.8%) among older adults who reported medical toll as a bulwark to seeking health care when compared to older adults who did non report medical cost as a barrier (5.5%). Later adjusting for all covariates, we found that older adults who reported medical cost as a barrier to seeking health intendance were twice more likely to report electric current depressive symptoms compared to those who did not study medical cost as a barrier to seeking health intendance. In addition, we as well constitute that older adults with the following socio-demographics: females, Blackness non-Hispanics, Hispanics, and loftier school or less education; wellness indicators: "Off-white/Poor" full general health, smokers, and use of special equipment due to a wellness trouble; and health care indicators: non having a health program, and no annual checkup, were significantly more likely to written report medical cost every bit a barrier to seeking health care. This finding is consistent with prior studies that take identified socio-demographic characteristics associated with out-of-pocket medical cost [15, 31, 32].

Clan between medical price every bit a bulwark to seeking health care and symptoms of current depression

One of the most common barriers to seeking health care is out-of-pocket medical toll [33]. In particular, amidst older adults with chronic conditions, the burden of out-of-pocket medical cost is a major business [34,35,36]. In this current study, though out-of-pocket health care expenses was not measured, consequent with previous studies [xix, 37,38,39], we establish that the proportion of older adults who reported medical price as a barrier to seeking wellness care increased with the number of chronic weather (Table 1). A plausible explanation could be that a significant proportion of medical cost may have to do with out-of-pocket expenses for medications and prescription drugs oftentimes required to manage chronic conditions [34,35,36, 39].

Empirical testify presented in the current study suggests that the burden of out-of-pocket medical price is significantly associated with symptoms of current depression, thus, taking a step further in our agreement of the consequences of out-of-pocket medical cost (toll-sharing) burden amidst older adults. This finding is consistent with previous studies which reported the association between financial strain in general and symptoms of depression among older adults [23, 24].

Several studies have reported that lack of wellness care coverage or type of coverage (e.g., Medicare just) would atomic number 82 to high financial burden [xix, 36, xl]. This finding was consistent in our study with 27.3% reporting medical cost as a bulwark for seeking wellness intendance among those without a health program compared to five.2% reporting the same among those with a wellness plan. However, despite having a health plan, the unadjusted prevalence of symptoms of current depression amidst older adults who reported medical toll every bit a bulwark for seeking health care was 18.8% [95% CI: 11.eight–25.7%]. Whereas among older adults without a health programme, the unadjusted prevalence of symptoms of current depression among those who reported medical toll every bit a barrier for seeking health intendance was 8.6% [95% CI: 2.two–15.0%]. This could exist because older adults with a health plan are more likely to use health intendance and as a issue might take to sustain more than out-of-pocket expenses compared to those without a health plan.

While nosotros don't take specific data about the type of wellness programme, to understand the extent to which having a health program mitigates the association between the brunt of out-of-pocket medical toll and the likelihood to study current depression after controlling for all socio-demographic and health related factors, nosotros examined the magnitude of this association stratified by health plan status. Among older adults who reported having a health plan, after adjusting for possible potential confounders, older adults who reported medical toll as a barrier for seeking health care were more than twice as likely to report current depression compared to those who reported medical price not being a barrier for seeking health intendance [AOR: 2.2 [95% CI: 1.5–3.4]); whereas amidst those who reported not having a health plan, the magnitude of this association was much augmented [AOR: 7.3 [95% CI: 2.2–22.4]). This finding suggests that the burden of out-of-pocket medical cost is significantly associated with symptoms of electric current depression though the magnitude of this association could be mitigated due to having a health program. As the prevalence of individuals with persistently loftier medical price burden is likely to surge in the hereafter [34], policies to reduce the burden of out-of-pocket medical cost among older adults may help address depression to some extent amongst the elderly and thereby reduce health intendance costs associated with depression.

Strengths and limitations

Although this study documents, using a nationally representative sample, a significant association between the individuals' burden of medical cost for wellness care and symptoms of depression amongst older adults, these findings are subject to limitations:

-

The cantankerous-sectional nature of the BRFSS data precludes us from drawing whatever causal relationship betwixt the brunt of medical toll and symptoms of current depression.

-

BRFSS information are based on self-report and therefore may exist subject area to call back-bias for certain types of responses.

-

Assay of data in this study did non consider social and emotional back up system among older adults. It is likely that social isolation in older adults might be a contributing factor to private's mental health [41, 42]. In improver, the assay did not account for annual income; approximately i out of 7 older adults reported every bit employed during the fourth dimension of the survey.

-

Information almost having a health plan was binary (Yes / No). Information nearly the type of health plan (due east.g., types of insurance coverage) would have shed more low-cal into the relationship between the burden of medical cost for health care and symptoms of current low.

-

Finally, since the data used in the electric current report are from 12 states in the 2011 BRFSS survey and is express to not-institutionalized older adults, the findings may non exist generalizable to all older adults in the U.S.

Despite these limitations, this report documents an important finding that has policy implications. To the all-time of our knowledge, this is the first report to report a significant clan betwixt individuals' brunt of medical cost for health care and symptoms of low.

Conclusions

In determination, findings from this study suggest that older adults (≥ 65 years of age) who experience the brunt of medical cost for health care are significantly more likely to written report symptoms of depression. Having a wellness plan might help mitigate the association between burden of medical cost for wellness care and symptoms of depression. Health care professionals and policymakers should consider effective interventions to amend access to health care amid older adults. Such efforts may help address the mental health concerns such as low among the elderly and thereby reduce the cost brunt associated with information technology and improve health outcomes. Further research is necessary to confirm the findings from this report and to understand how older adults manage their comorbid atmospheric condition which puts on them a huge brunt of out-of-pocket medical cost to deal with.

Availability of data and materials

Datasets can exist obtained from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- BRFSS:

-

Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance Organisation

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- U.S:

-

United States

- UOR:

-

Unadjusted Odds Ratio

References

-

Gill J, Moore MJ. The State of aging & health in America. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013.

-

Ortman JM, Velkoff VA, Hogan H. US Census Bureau. An aging nation: the older population in the United States. Available at: https://world wide web.census.gov/prod/2014pubs/p25-1140.pdf. Accessed 9 Oct 2017.

-

Buttorff C, Ruder T, Bauman M. Multiple chronic weather in the United states. Santa Monica: RAND Corporation; 2017.

-

Part of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion [ODPHP], Salubrious People 2020. Older adults 2016.

-

Allan C, Valkanova V, Ebmeier 1000. Depression in older people is underdiagnosed. Practitioner. 2014;258(1771):19–22 2-3.

-

Manthorpe J, Iliffe S. Depression in Later on Life. London; Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2005.

-

Blazer DG. Low in late life: review and commentary. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Med Sci. 2003;58(3):M249–65.

-

Lopez Advertizement, Murray CC. The global burden of disease, 1990–2020. Nat Med. 1998;iv(11):1241.

-

Chang-Quan H, et al. Health status and risk for depression among the elderly: a meta-analysis of published literature. Age Ageing. 2009;39(1):23–thirty.

-

Lenze EJ, et al. The association of late-life depression and feet with physical disability: a review of the literature and prospectus for hereafter enquiry. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;ix(2):113–35.

-

Prince MJ, et al. Social support deficits, loneliness and life events every bit risk factors for depression in old age. The gospel oak project Half-dozen. Psychol Med. 1997;27(2):323–32.

-

Blazer D, et al. The clan of age and depression among the elderly: an epidemiologic exploration. J Gerontol. 1991;46(6):M210–5.

-

Harris T, et al. Predictors of depressive symptoms in older people—a survey of ii general exercise populations. Age Ageing. 2003;32(5):510–8.

-

Vink D, Aartsen MJ, Schoevers RA. Take chances factors for anxiety and depression in the elderly: a review. J Affect Disord. 2008;106(one–ii):29–44.

-

Crystal S, et al. Out-of-pocket health intendance costs amidst older Americans. J Gerontol Soc Sci. 2000;55(1):S5I–62.

-

Goins RT, et al. Perceived barriers to health care admission amid rural older adults: a qualitative study. J Rural Health. 2005;21(3):206–thirteen.

-

Goldman DP, Zissimopoulos JM. Loftier out-of-pocket wellness care spending past the elderly. Health Aff. 2003;22(3):194–202.

-

Piette JD, Heisler K, Wagner TH. Issues paying out-of-pocket medication costs amongst older adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):384–91.

-

Schoenberg NE, et al. Brunt of common multiple-morbidity constellations on out-of-pocket medical expenditures among older adults. Gerontologist. 2007;47(4):423–37.

-

Bock J-O, et al. Touch on of depression on health care utilization and costs amid multimorbid patients–results from the multicare cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e91973.

-

Kalsekar I, et al. The effect of depression on health care utilization and costs in patients with blazon ii diabetes. Manag Care Interface. 2006;xix(3):39–46.

-

Welch CA, et al. Low and costs of health intendance. Psychosomatics. 2009;fifty(four):392–401.

-

Krause Due north. Chronic financial strain, social support, and depressive symptoms among older adults. Psychol Aging. 1987;2(2):185.

-

Mendes De Leon CF, Rapp SS, Kasl SV. Fiscal strain and symptoms of depression in a community sample of elderly men and women: a longitudinal report. J Crumbling Health. 1994;6(4):448–68.

-

Remler DK, Greene J. Price-sharing: a blunt instrument. Annu Rev Public Wellness. 2009;30:293–311.

-

Baird KE. The financial brunt of out-of-pocket expenses in the United States and Canada: How different is the United States? SAGE Open up Med. 2016;iv:2050312115623792.

-

Centers for Disease Command and Prevention. Behavioral Take a chance FactorSurveillanceSystem operational and user's guide. Version three.0. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/pdf/userguide.pdf. Published March 4, 2005. Accessed 19 Nov 2017.

-

McGuire LC, et al. The patient health questionnaire 8: current depressive symptoms amid United states older adults, 2006 behavioral risk factor surveillance arrangement. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(4):324–34.

-

Kroenke M, et al. The PHQ-viii as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2009;114(ane–three):163–73.

-

Frances A, Pincus HA, First M. Diagnostic and statistical transmission of mental disorders: DSM-Four. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

-

Davidoff AJ, et al. Out-of-pocket health care expenditure burden for Medicare beneficiaries with cancer. Cancer. 2013;119(6):1257–65.

-

Desmond K, Rice T, Cubanski J, Neuman P. The burden of out-of-pocket health spending amidst older versus younger adults: Analysis from the consumer expenditure survey, 1998–2003. Medicare Issue Brief. No. 7686. Menlo Park, C.A.: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2007.

-

Fitzpatrick AL, et al. Barriers to health care admission among the elderly and who perceives them. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(10):1788–94.

-

Cunningham PJ. Chronic burdens: the persistently high out-of-pocket health intendance expenses faced by many Americans with chronic conditions, vol. 63. New York: Commonwealth Fund; 2009.

-

Hwang W, et al. Out-of-pocket medical spending for intendance of chronic weather condition. Health Aff. 2001;xx(6):267–78.

-

Sambamoorthi U, Shea D, Crystal S. Total and out-of-pocket expenditures for prescription drugs among older persons. Gerontologist. 2003;43(3):345–59.

-

Soni A. Out-of-Pocket Expenditures for Adults with Health Care Expenses for Multiple Chronic Conditions, United states Noncombatant Noninstitutionalized Population, 2014. Statistical brief #498. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2017.

-

Paez KA, Zhao L, Hwang Westward. Rising out-of-pocket spending for chronic conditions: a ten-year trend. Wellness Aff. 2009;28(i):fifteen–25.

-

Fahlman C, et al. Prescription drug spending for beneficiaries in the terminal Medicare plus choice year of life. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(iv):884–93.

-

Johnson RW, Mommaerts C. Are health care costs a burden for older Americans? Retirement Policy Programme Brief Serial, vol. 26; 2009.

-

Oxman TE, et al. Social back up and depressive symptoms in the elderly. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135(4):356–68.

-

Santini ZI, et al. The association betwixt social relationships and depression: a systematic review. J Bear upon Disord. 2015;175:53–65.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to admit the participants in the 2011 BRFSS survey.

Funding

No external funding was secured for this study.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

VKC conceptualized and designed the study, designed the analytic program, conducted the analyses, drafted, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. ETC conducted the initial analyses, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and canonical the final manuscript equally submitted.

Respective writer

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

No administrative permissions were required to access the raw data. This study was exempt from review by Kent Country Academy'south IRB because BRFSS information are publicly available and deidentified.

Consent for publication

Non applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Boosted file 1:

Table S1. Estimated Odds Ratio (95% CI) for Current Depressive Symptoms (PHQ-eight Score ≥ 10) among Adults Aged 65 and Older (n = 24,018). (DOCX xx kb)

Rights and permissions

Open up Admission This article is distributed under the terms of the Artistic Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original writer(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Artistic Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/nix/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this commodity, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cheruvu, V.K., Chiyaka, Eastward.T. Prevalence of depressive symptoms among older adults who reported medical cost as a barrier to seeking health intendance: findings from a nationally representative sample. BMC Geriatr 19, 192 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1203-2

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1203-ii

Keywords

- Medical cost

- Out-of-pocket expenses

- Low

- Current depressive symptoms

- BRFSS

Source: https://bmcgeriatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12877-019-1203-2

0 Response to "Peer Reviewed Articles on Depression in the Elderly"

Postar um comentário